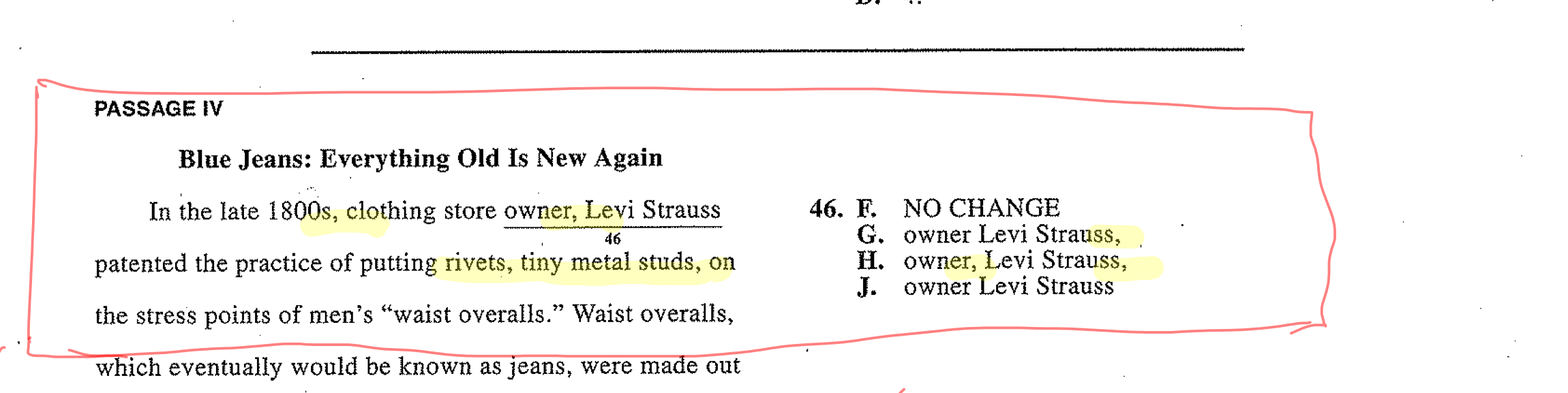

There are a number of questions in the ACT English section that test your understanding of appositives. But what, exactly, is an appositive? To answer that, we first have to understand what the word 'apposition' means. 'Apposition' really just means 'putting something in close proximity with something else'.

In our case, these two 'somethings' would be a name and a phrase, i.e. a bunch of words. So the definition of an appositive is 'a bunch of words that is put next to a name in order to give additional information about the name'. It also works the other way around: an appositive is a name that is put into close proximity with a bunch of words in order to give additional information about the bunch of words.

To be more concrete, we could take the phrase 'the great English writer' and put it into apposition with the name 'William Shakespeare' to make provide more information about William Shakespeare.

What can be tricky is to understand whether the appositive in question is essential or non-essential. The status of the appositive is important because it determines whether the appositive in question will need to be set off by commas or not. The general rule is: Only non-essential appositives need to be set off by commas. People get very confused about this. What's essential? What's non-essential? Is that not something subjective? So let's try to get some clarity right from the start.

How do we determine whether an appositive is essential or not? In fact, it's quite easy. You just need to think whether the phrase that goes with the name excludes any other name. If it does, the appositive will be non-essential.

What does that exactly mean? That's where the confusion can start. But no need for that at all. Let's go back to the example about Shakespeare. What you need to ask yourself is: does the phrase 'the great English writer' exclude anyone else than Shakespeare? The answer is obviously no. There are many great English writers; Shakespeare is only of them, so the appositive offers vital clarification of a quite vague phrase. In other words, the appositive is essential.

How, you might ask, can we make 'William Shakespeare' an non-essential appositive? We simply need to find a phrase that is more narrow in scope. How can we narrow it down to good old William? A example would be to use the phrase 'the author of Hamlet'. There is only one author of Hamlet. There can be no other name in apposition than 'William Shakespeare'. Here, the name becomes non-essential. Used in a complete sentence, the correct punctuation would be 'the author of Hamlet, William Shakespeare, was born in Stratford-upon-Avon'. The name needs to be set off by commas.

It's important to understand that it does not matter whether you know who the author of Hamlet was. The only thing that matters is that the phrase obviously narrows down the possible options to just one (there can be only one author), making the appositive non-essential.

Considering this concept of limitation, you always have to look out of superlatives (i.e. forms like best, greatest, etc.) since they automatically exclude any other option. If we were to start the sentence with 'the greatest Elizabethan playwright', the name 'William Shakespeare' would automatically come between commas.

The important fact is that it really doesn't matter whether you would agree with the statement that Shakespeare was the greatest playwright of the period. In the context of the sentence, there can be only one name since there can obviously be only one 'greatest'. In the sentence 'the greatest Elizabethan playwright, William Shakespeare, was born in Stratford-upon-Avon' the name will therefore come between commas.

You can also replace the name and make the sentence 'the greatest Elizabethan playwright, Christopher Marlowe, was murdered under mysterious circumstances'. The name still comes between commas; the appositive is still essential. Some people might disagree, but the appositive doesn't care.

This leaves us with three rules of thumb:

1. If you go from unspecific phrase to name, the name will not need to be set off by commas.

The author (unspecific) William Shakespeare wrote great tragedies.

2. If a sentence starts with a name (i.e. the most specific thing there is) and then phrase (less specific than a name) give more information about the name, the phrase will be non-essential and therefore need to be set off by commas.

William Shakespeare (very specific), a prolific writer of plays (less specific), remains today a very mysterious character.

3. If a very specific bunch of words comes before a name, the name will come between commas.

The greatest of all English tragedies (very specific), Hamlet, was written sometime between 1599 and 1602.

Contact us here for more info about ACT prep with Essai.